Shumka x AIRS on Pancouver: ‘Kelsie Grazier fosters curiosity, compassion in elementary classrooms with AIRS program’

By Perrin Grauer

In collaboration with the Vancouver School Board and Shumka Centre for Creative Entrepreneurship, AIRS brings local artists to BC classrooms to teach visual arts to children.

As Shumka x AIRS’ artist-educator in residence. Kelsie Grazier teaches 11 classes of students each week ranging from kindergarten to Grade 7 (Photo by Perrin Grauer)

Shortly before 9 a.m. on a grey, autumn Tuesday, artist Kelsie Grazier arranges 27 chairs in a circle in the middle of a quiet room in south Vancouver. On the floor, she lays the same number of wooden disks, topping each with a small stone.

The fluorescent overheads have been switched off, and the window coverings drawn. The white walls are cast in amber by the glow of a handful of shaded lamps and strings of glimmery lights. Hanging branches and houseplants draw shapes in warm shadows across the drop ceiling.

Minutes later, 27 children march into the room and take a seat, chatting or hushed, animated or still. These are Grade 7 students at Pierre Elliott Trudeau Elementary School, and this is their classroom.

Tucked away on the north side of the East Vancouver school, the classroom is home to the 2023 Shumka x AIRS program. Developed to recognize the ongoing relationship between Emily Carr University and AIRS (Artist in Residence Studio) Society since 2019, the year-long partnership was designed to award an Emily Carr alum with a paid, 24-week residency at a Vancouver elementary school.

Kelsie, a multidisciplinary, BC-based artist, is Shumka x AIRS’ artist-educator in residence. Each week, she’s been teaching 11 classes of students ranging from kindergarten to Grade 7.

Today, due to the unyielding West Coast cloud-cover, she’s had to scrap her plan to bring the atmospheric shimmer of a camera obscura beaming in through the blinds. Instead, she’ll lead her students in a “blind contour” drawing. The exercise will see students draw a self-portrait with their eyes closed, using their sense of touch as a guide.

But first, Kelsie sits with her class for a check-in. After giving students a chance to reflect on how they’re feeling, she asks each of them to choose a stone. She takes them through a short series of deep breaths, and then guides them in a “noticing exercise”. This involves letting go of one’s noisy thoughts, and simply observing the stone in one’s hand. Is it rough? Smooth? Does it have stripes? Speckles? Is it heavy or light?

Both the “noticing” and “blind contour” activities are related to mindfulness. Both are about connecting students more closely with their own attention and body.

Most modern primary-school curriculum is aimed at outcome-based learning. Students are taught to reliably pursue common goals, analyze content and demonstrate their knowledge via standardized assessments. Giving them an opportunity to embrace risk-taking, vulnerability and uncertainty can serve as a vital counterpoint to the rest of their syllabus.

“When they don’t necessarily know what the outcome will be, it forces them to get outside their comfort zone,” Kelsie tells me. “My hope is to teach them process over perfection and to listen to their intuition in terms of creating.”

Operating in uncertainty is particularly challenging for 12-year-olds, Kelsie adds. At that age, kids are constantly fretting over what their peers think. And they’re deeply concerned with fitting in. So being given space to trust themselves on their own terms can offer a strong foundation for personal growth through their adolescence.

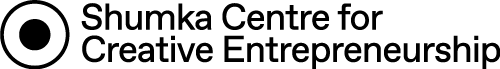

The students take their chairs to a pair of long tables and lay out fresh paper and sharpened pencils. One brave soul volunteers to attempt his drawing standing up, positioning himself next to a roll of paper taped to the wall. Students touch their fingers to their nose, ear, chin. And then they close their eyes and begin to draw.

(Photo by Perrin Grauer)

This is the real world

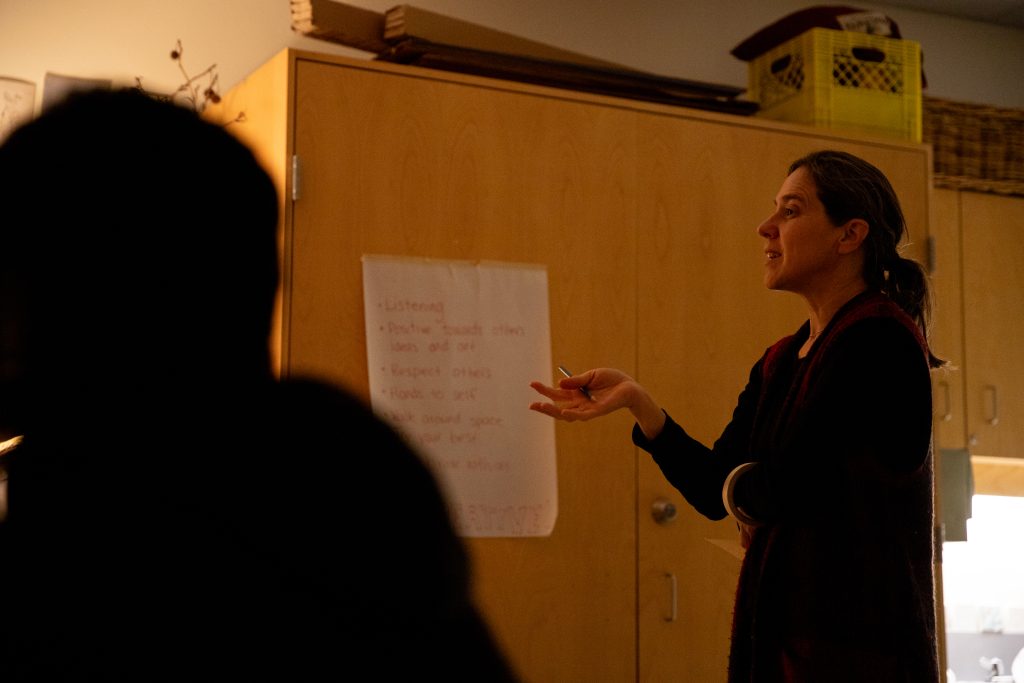

Maggie Milne Martens, AIRS’ co-founder and artistic director, is on hand in the classroom today. As questions bubble up, she joins Kelsie in keeping students engaged and offering gentle encouragement.

She notes that although arts are part of core curriculum in BC, many public elementary schools lack the expertise and funding to support arts programming. Yet time and again, research shows the long-term benefits young learners receive from such programs. Confidence, resilience, empathy, compassion, respect for cultural diversity, reduced anxiety and a developed capacity to imagine a better future are all nourished by arts education.

This is crucial in a context where global conflict, wealth inequality, social injustice, and the climate crisis are woven into daily life, she continues. Children are keenly aware of such issues. Giving them tools for creative problem-solving can provide empowerment and agency in the face of overwhelming challenges.

“This is the real world,” Maggie says, gesturing around the classroom. “It’s not like children are separate from the public sphere, and then at some magical point, they become real people. They already are. They’re affecting change and forming ideas about what’s important and valuable. And art is critical for understanding the self and relevant issues in the world, as well as what it means to be a community and embrace difference.”

AIRS’ co-founder and artistic director, Maggie Milne Martens, helps keep students engaged. (Photo by Perrin Grauer)

Dorothy Watkins is the former principal of Seymour Elementary—a former AIRS residency school. Dorothy notes the confidence and curiosity children develop through arts learning provide durable resilience in navigating and communicating broader situational challenges, even ones as dire as food or housing insecurity.

“Having a studio space and an artist in residence who explores artistic expression and teaches art-process skills gives such support and encouragement to these children,” Dorothy says. “Students are learning to express themselves and have the opportunity to show their knowledge through art.”

Jim Munk is the principal of Pierre Elliott Trudeau Elementary. He notes that empowerment as an outcome can also be credited to Kelsie’s choices as an educator.

“Her approach is inclusive and allows the students to be creative and to develop their own self-awareness in regard to the arts,” Jim says. “Kelsie has been instrumental in guiding our students to develop confidence in their self-expression.”

(Photo by Perrin Grauer)

Encounters with difference

As I walk around the classroom, children peek out from between knitted fingers and laugh. “It looks just like me!” they say, jokingly. The faces in their drawings are predictably wacky. The likeness of the finished work to their actual faces is, of course, beside the point. They compare work with their classmates, all wide eyes and smiles, grab fresh sheets of paper, and close their eyes again.

For Kelsie, learning to embrace quiet focus has been a transformational personal and artistic practice as well as an educational touchstone. Diagnosed with mild-to-moderate hearing loss at age three, she would become completely Deaf as an adult. As she lost her hearing, Kelsie also began suffering from tinnitus—an insistent, often painful sound that has no external source, meaning no one else can hear it.

“I was studying in my master’s program while listening to this awful ringing like those old-school red fire alarms and radio static on full blast,” she tells me. “I found it extremely challenging and exhausting, and I started to withdraw. And I withdrew into my art as a way to meditate and be mindful and get away from this constant sound that was making it hard to sleep.”

Kelsie drew white lines over and over. This exercise forced her “to be in the present moment”—a common strategy for managing tinnitus, which has no known cure.

Kelsie began learning sign language and became a part of the Deaf community. She quickly realized how important such fellowship could be for combatting the “isolation and desperation so many people have when they lose their hearing as adults.” She would later receive a cochlear implant—a surgery that does not restore hearing, but can help users perceive sounds by directing electrical signals through a device to the brain.

Her art practice became informed by these experiences. She now aims to be a “bridge between the Deaf and hearing worlds,” she says. Her recent solo show, Unstoried Self, at the Vernon Public Art Gallery addressed this aim specifically. But so does the way she starts her classes by seating students in a circle, she notes. This formation is a common communication strategy in the Deaf community for ensuring equality and visibility.

These and many other principles are part of what she brings to her practice as an educator. She adds that providing an “encounter with difference” teaches students “tools for the ways they conduct and carry themselves in their own communities”. Arguably, this outcome is more potent than any technical skill they might learn.

“Embodying who I am with the students is important,” she says. “And in this space, I’m hoping to reflect my values and a sense of calm and mindfulness that the students can impart into the rest of their lives.”

An exhibition of the students’ artworks, which will debut at the school and at Emily Carr University in spring, 2024, will give them an opportunity to reflect with pride on the achievements that can be won by embracing those values.

(Photo by Perrin Grauer)

The perceptiveness of children

With class-time nearing its end, Kelsie begins collecting drawings and taping them to the east wall. Students move their chairs to view their collection. Kelsie asks them to come up with one question about the exercise. Not an answer, she clarifies. Just a question. After a period of silence, they begin to wonder aloud.

“Why did I start in the centre of my face?” asks one student. “Why is my drawing so small?” asks another. More questions come as the students intuitively realize they’re being given a chance to interrogate the assumptions and frameworks that underwrote their own engagement over the past hour.

This, Maggie notes, is where the exercise becomes “existential”. It’s a demonstration of how the arts serve as a “deeply human way of expressing, being and forming connections and relationships in the world—as meaning-making for the self and for society in general”.

Which, prior to having sat through this class, would not have sounded to me like a lesson you could teach in elementary school.

Kelsie, herself now mother to a three-year-old child, knows differently.

“When they’re given permission to notice things and just say what they think, the perceptiveness of children is amazing,” she says.

You can find this article on Pancouver